2025-04-21

Kathmandu’s Air Is a Crisis — So Why Are We Still Silent?

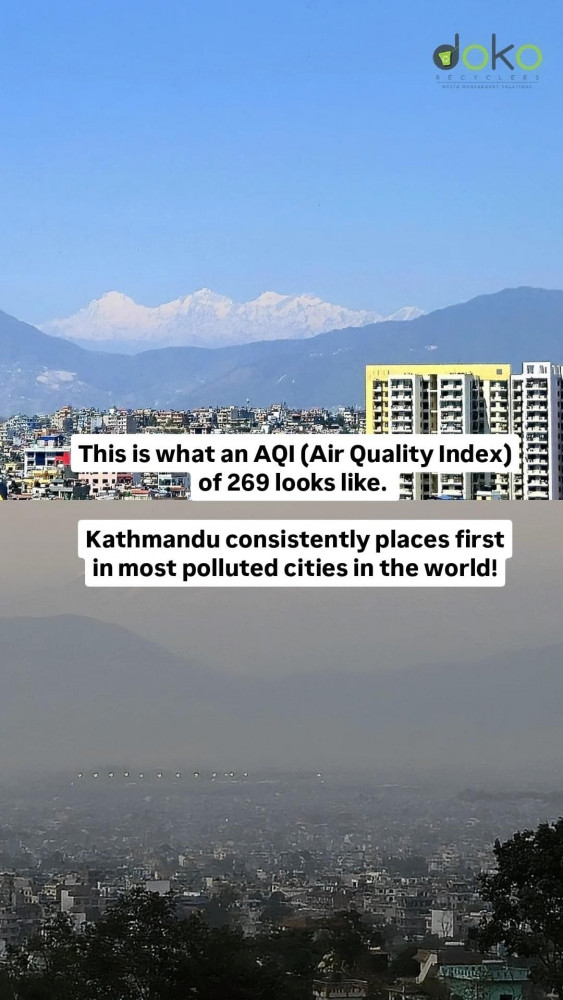

This April 3, Kathmandu ranked among the most polluted cities in the world. On that day, the Air Quality Index (AQI) in the valley surged to 348, entering the "hazardous" category. In the days that followed, the numbers stayed dangerously high, often remaining well above the levels considered safe for human health. The valley was shrouded in a thick haze, the air heavy and suffocating. Walking outside left a gritty taste in the mouth, a burning sensation in the eyes, and a tightness in the chest.

But this is not a new phenomenon. Kathmandu’s air pollution crisis has been decades in the making — a slow-motion disaster fueled by neglect, unchecked urbanization, and a lack of political will. To understand how dire the situation has become, we must look back at what the city once was—and how we got here.

Kathmandu’s Lost Clean Air

Older residents remember a different Kathmandu — one where the air was crisp in the mornings, the Himalayas were visible year-round, and the scent of blooming champas and pipal trees overpowered any urban odors. In the early 2000s, the valley’s air was relatively clean, with pollution levels far below today’s hazardous standards. The city was smaller, greener, and quieter, with fewer vehicles and more open spaces.

Back then, pollution was seasonal, mostly from winter wood fires and occasional dust storms. But as Kathmandu expanded—swallowing farmland, cutting down trees, and paving over its waterways—the environment began to deteriorate. The 1990s marked the beginning of rapid, unplanned urbanization. Brick kilns, diesel generators, and an explosion of motorbikes and cars turned the city into a pollution hotspot. By the early 2010s, Kathmandu’s air quality was already among the worst in South Asia on many days.

The Tipping Point: How Did We Get Here?

Explosion of Vehicles:

In the early 2000s, there were far fewer vehicles in Nepal. Today, there are over 4.5 million registered vehicles nationwide, with nearly half concentrated in the Bagmati Province, which includes Kathmandu Valley. Many vehicles are old, poorly maintained, and run on low-quality fuel. The government’s failure to enforce emission standards means black smoke-belching trucks, tempos, and motorcycles dominate the streets.

Unchecked Construction & Dust:

Kathmandu is a city perpetually under construction. Buildings rise without dust control measures, and roads are dug up and left uncovered, releasing clouds of fine particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) into the air. The ongoing infrastructure projects, while necessary, lack environmental safeguards, worsening air quality, especially during the dry season.

Open Burning & Waste Mismanagement:

Despite bans, open burning of garbage remains widespread. Plastic, rubber, and organic waste are set ablaze in alleys and open lots, releasing toxic fumes.

Vanishing Green Spaces:

Kathmandu once had sprawling gardens, ponds, and tree-lined boulevards. Today, concrete has replaced greenery. Urban parks are few and far between, while deforestation in the surrounding hills has worsened dust storms and landslides. The loss of natural wetlands—nature’s air filters—has left the city vulnerable.

Transboundary Pollution & Wildfires:

While local factors dominate, Kathmandu also suffers from pollution drifting from elsewhere. During spring, wildfires in Nepal’s forests — with hundreds of incidents already reported in early April 2024 — and agricultural burns in northern India cover the valley in smoke. Climate change has intensified the frequency and severity of these fires.

The Human Cost of Breathing Dirty Air

The consequences are visible in our hospitals and homes: rising cases of asthma, chronic bronchitis, strokes, and lung cancer. Thechildren, the elderly, and those with respiratory or cardiac conditions are at severe risk. Studies have even shown that prolonged exposure to high pollution levels reduces cognitive development in children.

The economic burden is staggering. According to the World Bank air pollution costs Nepal around 4.5% of its GDP each year due to healthcare costs and lost productivity. In a country grappling with poverty and development challenges, this is an unsustainable loss.

Why Is There No Urgency?

Despite the worsening crisis, the response has been largely cosmetic. The government has introduced few meaningful emergency measures: no traffic bans on heavily polluted days, no real crackdown on open burning, and no serious emission enforcement. Policies such as Vehicle Emission Standards exist mostly on paper, not on the streets.

Public concern is growing but not nearly at the pace needed. Many still see pollution as an unavoidable part of development. Politicians make promises, but follow-through remains absent. International organizations fund studies and issue reports, but visible change on the ground is rare.

What Can Be Done?

The problem is human-made, and the solutions are too — if we have the courage to act:

We Must Stop Accepting the Unacceptable

Kathmandu’s air pollution isn’t a natural disaster—it’s the result of human choices. And choices can be reversed. Clean air is not a luxury; it’s a basic human right.

If we stay silent and passive, we’re condemning ourselves and future generations to live in an increasingly hostile city.

This is not just about one polluted day in April.

It’s about the future of Kathmandu itself.

The time for denial is over. The time for action is now.

Pragya Neupane, Senior Partnerships and Grants Associate